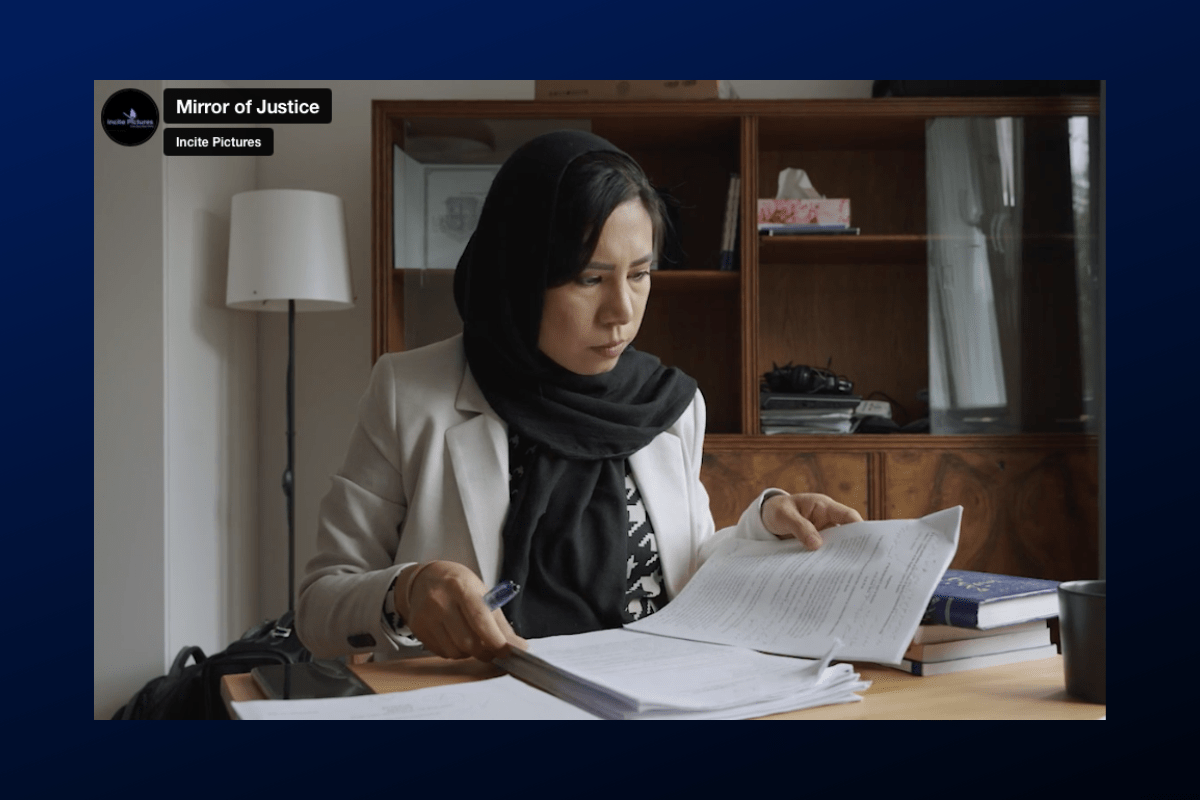

Duke Law School will welcome Judge Tayeba Parsa of Afghanistan as the first Bolch Judicial Institute Rule of Law Judicial Fellow in May 2023. Judge Parsa was among 250 women judges in Afghanistan, having served for a decade as a judge in the country’s commercial, civil, and public rights courts. She was serving as a judge in the Commercial Division of Appellate Court of Kabul Province in August 2021 when she was forced to flee for her life as the Taliban took power.

As the Bolch Rule of Law Judicial Fellow, Judge Parsa will begin to rebuild her legal career outside Afghanistan. The fellowship will allow her to study, teach, conduct research, and pursue new educational and professional opportunities with support from Duke Law and the Bolch Judicial Institute.

Leaving Afghanistan

When the Taliban re-claimed power across Afghanistan in August 2021, they threatened to kill those who supported the previous democratic government, which was built with U.S. support over nearly 20 years. Because of the Taliban’s harsh stance toward women, the country’s women judges were in particular danger. Many immediately went into hiding and burned their law degrees and case documents to erase evidence of their work to advance the rule of law.

With heroic help from the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ), which helped to arrange her escape flight and temporary refuge, Judge Parsa was among the few women judges who successfully escaped Afghanistan in the days immediately following Kabul’s fall to the Taliban. (The IAWJ has since rescued more than 200 women judges and is still working to evacuate all who remain. The organization’s efforts were honored with the 2023 Bolch Prize for the Rule of Law.)

Judge Parsa described her escape in a Judicature article in late 2021:

When the provinces were falling, one by one, we decided to leave and escape. My father called me and told me, “Do not come home for now, because there are Taliban in the checkpoints. They may search your car and discover your identity.” He said, “Do not drive yourself because even if they do not search your car your driving [as a woman] may make them angry.” . . .

I was in the car until that night. I saw that soldiers and police took off their uniforms to hide their identity and job. I felt I was trapped, and I was afraid of not only the Taliban but also criminals and thieves who may abuse the situation. Finally, my husband drove me home, and we did not come out until three days. During these three days, I was in touch with the IAWJ and other Afghan women judges. I was collecting my documents to hide them and destroying case notes to hide my identity. I was the first judge who received a call from a Polish lawyer about evacuation, because of an interview I gave against the Taliban. I never had wanted to leave the country and my job, but I was a female judge from the minority of Hazaras and the minority of Shia community, and I had been in touch with foreigners, which Taliban would consider an unforgivable crime. If I remained, I am certain I would have been killed. . . .

But leaving was painful. I felt I had lost all I had achieved. We didn’t want the Taliban to find out we were leaving. So we would not carry packages. I only picked my documents and some legal books that I love and could not leave. There was a crowd behind the gate at the airport, and the Taliban were shooting and beating people. I was standing up behind the gate without food and sleep for 24 hours. Finally, I entered in the airport. My father and husband waited for their flights, 24 more hours. They didn’t eat or sleep for 48 hours.

Judge Parsa and her husband were able to evacuate to Poland, where they have lived with temporary refugee assistance from the Polish government as they navigated visa processes and welcomed their baby girl. Though they are grateful for the support they have received in Poland, living in limbo for 19 months has been difficult for both Judge Parsa and her husband, who worked in data management and human resources in Afghanistan. Now, as they make arrangements for their arrival at Duke in May, they are eager to begin the next phase of their lives.

“For me, losing my job was like losing my life,” said Judge Parsa. “I studied and practiced law with a passion for almost 17 years. When I arrived in Poland, I was happy for being alive for one day. The second day, when I saw that I cannot work in the field that I always loved, I felt ‘I am nothing.’ When I was a judge, I was never happy only because I had a good position and was able to make money and a comfortable life for myself and my family. I was so pleased because I was able to make a difference in the society, and I had direct impact on administering justice. For me, protecting rightful people and preventing justice from being undone by corruption in courts that were famous for their corruption was a holy fight that gave meaning to my life. So while I am alive, I do not give up. I fight for the rule of law, equality, and women’s and minorities rights, even from exile.”

Building Life Anew

As part of her fellowship, Judge Parsa will receive a modest stipend and will have access to a range of Duke resources and services as she begins to build her career in the law outside Afghanistan. She will be invited to attend all talks and events of the Bolch Judicial Institute and to audit courses and attend talks in Duke Law School’s Master of Judicial Studies program. She also will be able to join Duke’s Summer Institute in Law, Language, and Culture and other courses and programs offered at Duke Law School and Duke University. Five North Carolina women judges of the IAWJ have established a volunteer mentor committee and will advise Judge Parsa on her studies and career path.

In addition, Judge Parsa will be able to pursue her own research and scholarship into topics pertaining to the rule of law and women’s rights.

“I would like to do my research, improve my English, and study for master’s and PhD degrees in law,” Judge Parsa said. “I would like to build my knowledge of law and learn from my experiences in the United States and from other judges, to use my knowledge in order to be able to work in the field of law and for the future of Afghanistan. I would like to dedicate the knowledge that I get through this opportunity at Duke to the service of the people of Afghanistan, to rebuilding Afghanistan and bringing back the rule of law, equality, and justice to the people of Afghanistan.”